Blown Away

thoughts on Storm Goretti

I was seventeen when the Great Storm of 1987 hit our home in Kent. Back in those days storms didn’t have names (and all this were fields, far as the eye could see…). Most people know that the storm was famously pooh-poohed on BBC Weather the night before it hit by weatherman Michael Fish:

“Earlier on today apparently a woman rang the BBC and said she’d heard there was a hurricane on the way. Well, if you’re watching, don’t worry, there isn’t. But having said that actually, the weather will become very windy.”

I like to think that woman rang in and gave him hell the next day.

Being a teenager, I slept through the whole thing. I remember waking to see it was past 8.30am, leaping out of bed in a panic and running downstairs, shouting, “I’m going to be late for school!” My mother then showed me the devastation outside. “There won’t be any school today.”

Storm Goretti was more powerful than the Great Storm. Hardly surprising. The very fact that storms now have names should be enough to make us pay attention to the fact that we have more storms now than we used to.

We and our neighbours in West Cornwall have been spending this week trying to accept what has happened. For some people the storm was life-changing with trees falling through the roofs of houses and displacing families. Power was off for days, water supplies cut, roads shut and communications disturbed. For most of us it was upsetting seeing the landscape violently ripped up and transformed overnight, whether our homes had been affected or not. Some were quick to point out that Nature is good at restoring and healing herself. Others angrily posted comments about “not forgiving the trees” for the damage they had caused.

We were away on the night of the storm so had only our worst imaginings to deal with until we returned to assess things. We have lost over 30 big old trees, but the house has got away very lightly, so I feel I can’t complain.

But it is sad. Very sad. My heart is extremely heavy and sore as I walk around the garden and down through the woods and see mighty pines and one gorgeous ilex oak lying on their sides, their massive root boles tipped on end, huge craters left where once the trees stood. It does feel as though I am walking through a battlefield of fallen giants. If I stood in one of the craters, my head would not reach the top.

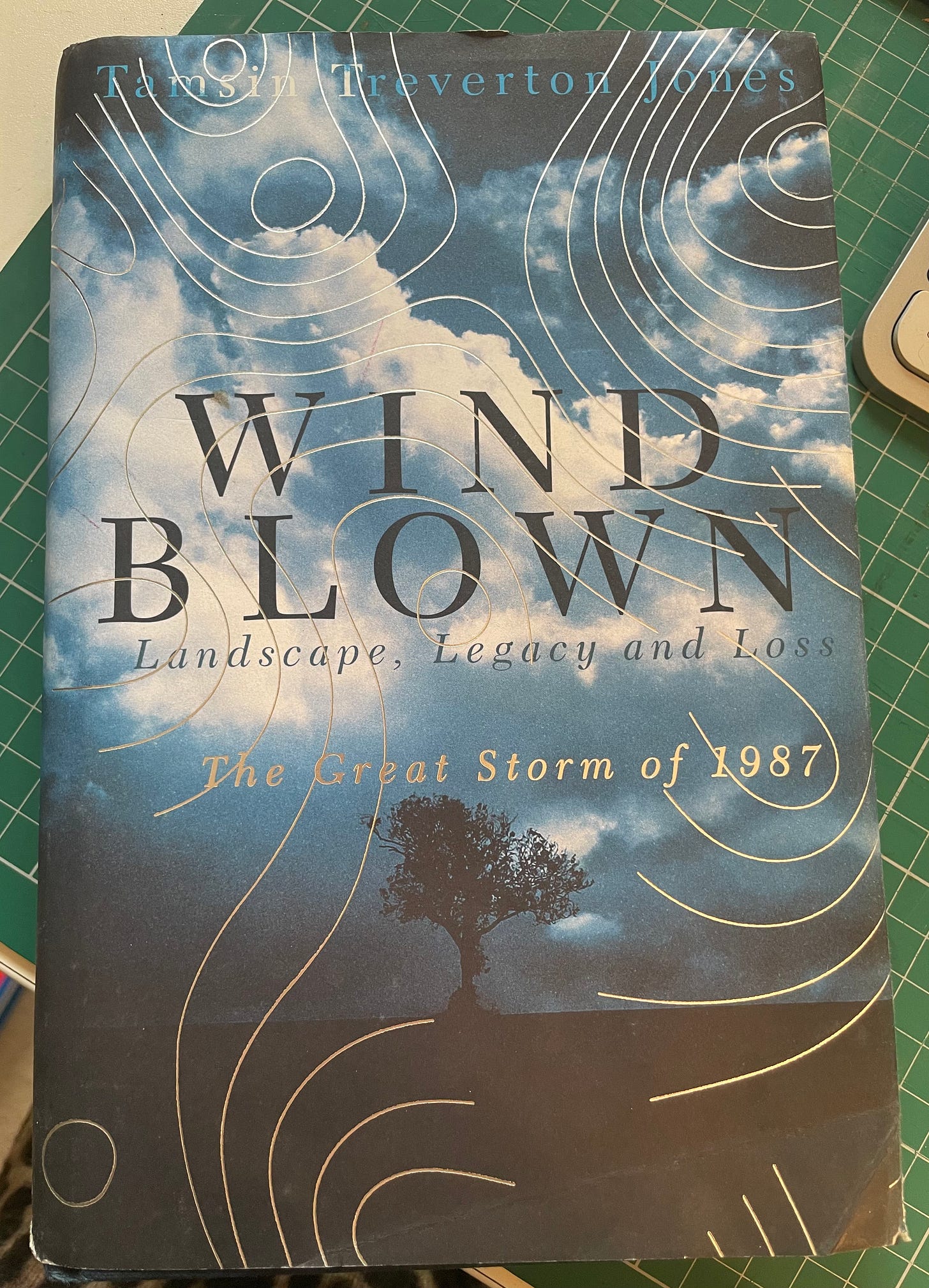

After the first recce, I remembered I had read a brilliant book about the Great Storm called Windblown by Tamsin Treverton Jones. Not only is she a Cornishwoman and writes beautifully about her connection to the landscape here, but in her book she has also perfectly summed up the emotions that took people by surprise after the 1987 storm. I remembered being moved by the book and also finding great solace in its optimism. So I dug it out and thought I’d share some passages with you today.

The most interesting part of the book, I feel, explores the annihilation of Kew Gardens back in 1987. I was too young and self-centred to care much at the time. I don’t think I had even been to Kew. I was much more concerned about being able to get back to my own life - and away from the claustrophobia of being housebound.

Reading the book now, and especially re-reading it after Storm Goretti, I am struck by the collective grief which Treverton Jones so movingly describes. She writes of a list of trees that were lost at Kew, all catalogued using their Latin names with lovingly noted descriptions of them alongside.

Perhaps it was the inky scrawl, the way the handwriting slanted on the page (a reminder that this happened before the widespread use of computers); perhaps it was the easy use and musicality of the Latin names or the way in which the individual characteristics of each tree were described with such familiarity that moved me as I read it. The lists were genuine tributes to the fallen, written by a human being in shock, with words and phrases that echoed with a crushed sense of bereavement. It was clear that, for all those who managed our parks and gardens, their shock and grief at the storm’s havoc and destruction were real.

Later in the book, this grief is balanced with the wonderful renewal which the botanists at Kew observed. An ancient tree, the Turner’s oak (a cross between an English oak and a holm oak created in 1783 by Mr Turner, a horticultural innovator from Essex) had been lifted by the storm, “like a plug, out of the ground, but instead of falling over, it dropped back into its pit and settled again, remaining upright despite its severely shaken roots” and months later, when inspected, workers at Kew “were surprised to find it in rude health”. It is still standing today. Treverton Jones explains:

This was natural disturbance in action: the violence of the wind had done the old tree a favour, it seemed. Its lift and resettlement during the storm had allowed air to circulate around the roots, de-compacting the bole, rejuvenating the hard, lifeless soil that had been pounded by lawn mowers and thousands of feet over the last 250 years, allowing oxygen to reach its complex underground life-support system.

Since Suzanne Simard’s Finding the Mother Tree was published in 2021 there has been an increased collective awareness of the role the mycorrhizal network plays in a woodland’s health and “communication” between trees. Treverton Jones writes of how the botanists at Kew thought of the trees “as family members; intrigued that trees live like humans do, in mutually reliant communities, supporting each other, as well as a web of biodiversity”.

So there is hope. Trees can recover, and if they don’t, they give back into the soil as they rot, and thus too provide habitats for insects and invertebrates and birds. I have to hold on to this as I walk through the woods and step over and under the fallen giants I have known for over thirty years. I have to hope that humankind has not made such a mess of things that Nature will not have the power to regenerate as much as she has the power to destroy. That we haven’t made her so angry that she no longer has the will to keep repairing herself.

As Treverton Jones says on looking at a lost avenue of trees:

“[it] suggested much more than straightforward natural regeneration. It felt like natural chaos: wild Nature, in all her anarchic, unsentimental glory.”

If nothing else, Storm Goretti has reminded us (and boy does it seem like we need constant reminders) that we are but tiny specks in the face of Nature’s power. And if we don’t listen, she roars.

Over thirty trees! So distressing and tragic.

Beautiful post - fallen giants...